A man from Nakhijevan who has been displaced twice does not lose hope—there will be a return to Nakhijevan and Artsakh

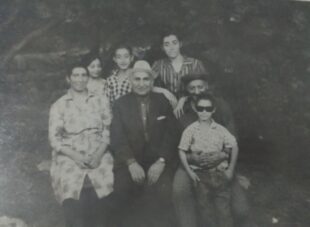

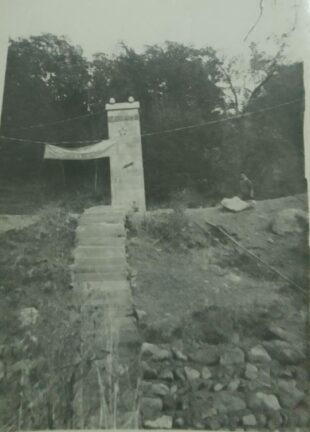

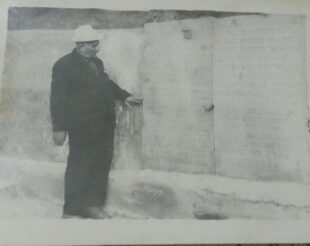

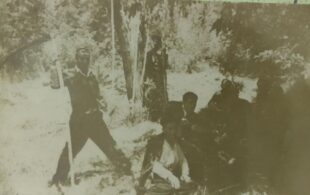

Goght, Alahi, Paraka, Ghazanchi, Bist… These are Armenian villages now under Azerbaijani control. Although Nakhijevan is in the hands of the enemy and its residents are scattered across various places in Armenia, they have not lost contact with one another. They often gather to reminisce about the happiest days spent in their birthplace. Conversations between our compatriots from Nakhijevan frequently take place in their native dialects: Bist residents speak in the Bist dialect, while Paraka residents use the Paraka dialect. My conversation partner, Mher Yesayan, is from the village of Bist in Nakhijevan. He shares stories of his days spent in Nakhijevan. Below, we also present photos from Mher’s personal archive that he managed to save and bring with him.

– Mr. Yesayan, you spent your youth in Nakhijevan. What activities were young people in Nakhijevan engaged in during those years?

– In Bist, there was an old man, and he was also my relative; his name was Hambardzum. We were young, and he was older, but he was known for his jokes. Most of his jokes were about his own life; they weren’t made up. As young people, we liked to ride our horses to one of the hills near the village, by the Red Monastery (we had called it that way because the stones were red). We would take cheese, lavash, and fruits with us, and we would sit there for hours by the flowing river, talking, sharing our plans for the future, falling in love and arguing… In short, we lived. Then we heard that Hambardzum’s chickens had died, and they had pulled out their feathers, while the dead chickens were thrown into a ravine not far from us. A little while later, those “dead” chickens came out of the ravine, completely naked, and they were running toward us. We called out, and Hambardzum came to take his naked chickens away. Later, it turned out that the chickens had drunk the mulberry vodka that Hambardzum had made instead of water and had fallen asleep. Hambardzum and his wife thought they had died.

– When you talk about the years you spent in Nakhijevan, your eyes shine; how did you manage to adapt and live in the same way far from your birthplace—in Artsakh?

– Artsakh and Nakhijevan have similarities; even the dialects are a bit alike. It wasn’t easy to leave Nakhijevan, but Artsakh welcomed us so warmly. At that time, Artsakh needed us; it was necessary to resettle the liberated Kashatagh. From Bist to Masis, from Masis to Goghtanik, and from Goghtanik to Kashatagh. Well, then from Kashatagh back to Masis again. It was difficult to experience two displacements; I felt the same pain in both cases. I do not lose my faith; both Artsakh and Nakhijevan will be liberated from the enemy.

– You said you do not lose your faith that the lost homeland will be liberated. After the liberation of Artsakh and Nakhijevan, where will you return to live?

– You are asking a difficult question. After all, both are mine, but probably to my birthplace, Nakhijevan. In the end, everyone returns home.

– Do you have any information about your home in Nakhijevan? Surely, Azerbaijanis live there now.

– Yes, I have information because after we were expelled from there, my father went to at least take a few belongings, but Azerbaijanis were already living in our home. They didn’t even allow him to approach the house. We still keep the property documents in hopes that justice will be restored. I also keep the property documents for our house in Artsakh. I believe that Artsakh will be liberated sooner. I will return to Kashatagh and wait for the liberation of Nakhijevan.

– What would you like to say to our compatriots?

– Love our homeland, even the places you have never seen. It’s difficult, but love it, because it is the lack of that love that diminishes the homeland you see every day. I am saying this as someone who has been displaced twice. Cherish every day you spend in your birthplace; do not abandon the villages. It’s also difficult, but we cannot empty our settlements; otherwise, God forbid, we will lose them, and it will be too late to understand the value then.

Seda Makaryan