Armenia no longer has any obligations toward Artsakh, only because the current leaders want to forget the past, says Vartan Oskanian

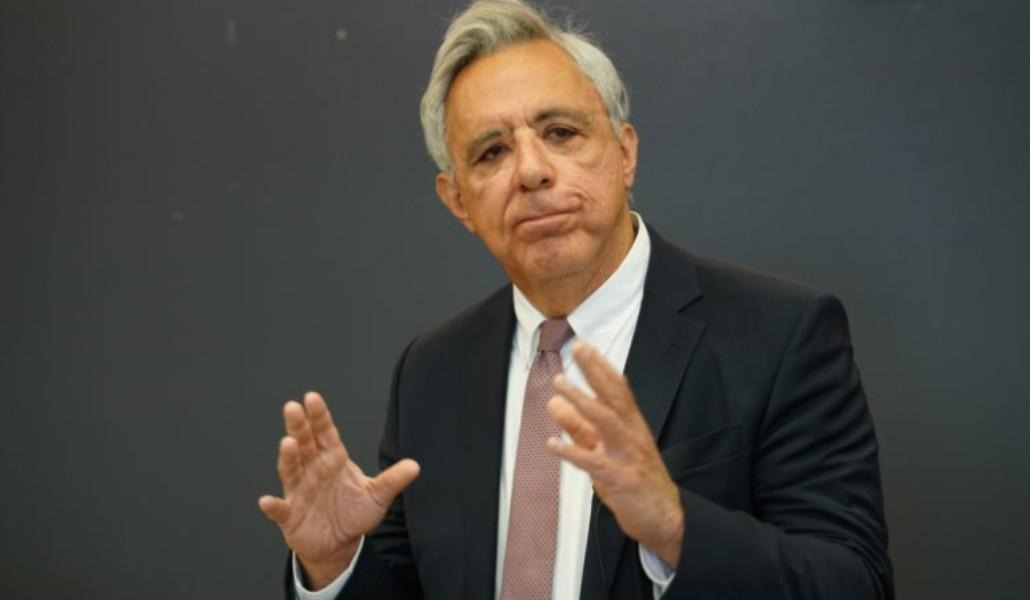

In the aftermath of the forced displacement of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh, many in Armenia seek answers—some out of grief, others out of guilt, and still others out of a desperate desire to forget, Vartan Oskanian, Former Foreign Minister of Armenia, writes.

“Among them, let us consider many 40-year-old men and women born in Nagorno-Karabakh and now living as refugees in Armenia. They were five years old in the early 1990s when the people of Armenia rose up demanding the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia. They remember none of it. They made no decisions. They bore no responsibility. And yet, they are now the ones who pay the price.

What was their sin? That they were born Armenian in Nagorno-Karabakh? That they trusted a nation and a state that once rallied around the idea that the people of Artsakh had the right to self-determination and were eventually to become an inseparable part of the Armenian nation?

Since 1991, every government of the Republic of Armenia has inherited the legal and moral responsibilities of the state, including its positions on national security and the protection of Armenian populations within and beyond its borders. Governments may change, leaders may come and go, but the state endures—and with it, its obligations. Sovereignty is not a reset button. The continuity of statehood imposes a duty to uphold the commitments, values, and causes that define a nation’s identity and historical trajectory.

It is morally indefensible and politically bankrupt to argue, as some do today, that the Republic of Armenia has no further responsibility toward Nagorno-Karabakh simply because its current leaders wish to distance themselves from the past. One cannot disown a cause that the state itself once championed.

What makes today’s abandonment even more egregious is the record of Nikol Pashinyan himself. During his early years in power, and even after the 44-day war, he was among the most hawkish of Armenian politicians on the issue of Artsakh. His rhetoric was unapologetically maximalist. He stood on the soil of Stepanakert and declared that “Artsakh is Armenia—period.” He left little room for negotiation and fed expectations not only among Karabakh Armenians but also among his own electorate that Armenia would never back down. And yet, it is under his tenure that the unthinkable occurred: the complete unraveling of Nagorno-Karabakh and the largest wave of Armenian displacement in recent history.

This is not a case of tragic inevitability. It is a case of incompetence and negligence, cloaked in revisionist justifications. It is an abdication not only of Armenia’s historical role but of its responsibility to its own citizens and compatriots.

Armenia may be governed by different administrations over time, but no government has the right to abandon a cause so central to the Armenian state’s identity and moral legitimacy. The story of 40-year-old refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh is not just their personal tragedy; it is the indictment of a government that has lost its way, conscience, and mind. And it is, above all, the political and moral failure of one man—Nikol Pashinyan—who had every opportunity, every mandate, and every warning, yet chose a path of denial, silence, and defeat.

History will judge him harshly. But our judgment must not wait for the verdict of time. It has already begun and must continue with greater resolve—through public discourse, in our collective memory, and in our firm conviction that the Armenian state cannot abandon the issue of Artsakh—an issue it was founded upon, and for which the current ruling authority bears responsibility and blame for today’s national tragedy,” Oskanian writes.